In today’s world, our race or ethnicity has an enormous effect on our personal identity. Races have histories, celebrations, countries of origin, cuisines, music styles and more. Mixed race, or biracial people have ancestries which come from different races. Technically, we are all multiracial as people boast of being “1/3 Italian, 1/5 French with a Grandma from Scotland” but the term mixed race/biracial refers to those with parents from two different races.

In today’s world, our race or ethnicity has an enormous effect on our personal identity. Races have histories, celebrations, countries of origin, cuisines, music styles and more. Mixed race, or biracial people have ancestries which come from different races. Technically, we are all multiracial as people boast of being “1/3 Italian, 1/5 French with a Grandma from Scotland” but the term mixed race/biracial refers to those with parents from two different races.

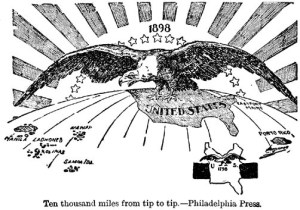

As racism declines and globalism increases, it is inevitable that the number of mixed race people around the world continues to grow. It is still, however, uncommon. In 2006, biracial people made up 2% of the United States population, 1.5% of the Canadian population. In 2005 in the UK, 3.4% of newborn babies were mixed race and by 2020 the mixed race population is expected to be Britain’s largest ethnic minority group with the highest growth rate. There is an estimated population of Anglo-Indians is 600,000, with the majority living in Britain and India. 2.4% of the 2007 Singapore population were mixed race. Although the most common mixed ethnicity is some form of black and white, the combinations are endless as the different kinds of races are endless.

Even though being from two different races means you have two different cultures to enjoy, the difficulty comes from the fact that technically, you are neither of those two races either. In a sense, mixed race people are born with a completely blank slate and they can create their own identities. Take me, Robyn, for example. My mother is black Caribbean and my father is white British. While my skin is brown, I am not black but neither am I white. I am both and yet neither and this fact is dealt with differently by each mixed race individual.

I have never connected myself with either the white or black cultures and my race has never even really been an important factor to me. I’ve always found that its other people who are more concerned about my race. 50% of the time people ask me “where are you from?” and, although I always know what they mean, I like to reply “Harrow” or “London” so they then ask “no, I mean like what country originally?” Then I explain my two different parents. The other 50% like to take a guess and BOY have there been some guesses. I’ve been mistaken for Indian, Greek, Middle Eastern, Native American, all of the Caribbean islands and just about all of the countries in South America. The only trouble I’ve ever found with being mixed race is when I am unable to fit in because I’m not a certain race. All over the world there are people who only hang out with and date those of their own race. One such experience when I was a teenager was when my Indian best friend ditched me to join a group of Indian girls just like her. I couldn’t appreciate or join in the Indian culture and it must have gotten tiresome for her. Losing a friend because I was mixed race was difficult to accept but for every Ying there is a Yang: there are many men in this world who specifically find mixed race girls HOT. Don’t know what it is, but they do! And I have never again found any trouble with my friends and have friends of all different races from all over the world. I also only take my race seriously when I get called Half-caste, the word I hate most in the whole world. I am NOT half of anything. Because mixed race people are so uncommon and the term half-caste has never been widely recognised as a racist term, people often use it in a completely neutral manner, not realising how offensive it can be. Think of it this way: the term “coloured” for black people isn’t widely recognised as racist as such, but if a black person got called that, odds are they would be offended and think “I’m not a frigging paint by numbers.”

There are also a high number of mixed race celebrities in this world and fame doesn’t prevent them having their own mixed race experiences.

Halle Belle recently told Lesley O’Toole how her White Liverpudlian mother Judith met her Black GI father Jerome, when he was stationed in England. She moved to America to marry him and they settled in Cleveland, Ohio. Initially, Berry’s parents lived in a black neighbourhood until Halle was four. However around this time they separated and Halle’s mother moved her and her sister Heidi to a white neighbourhood. ‘When we lived in the black neighbourhood, we weren’t liked because my mother was white. In the white neighbourhood, they didn’t like me because I was black. That was the beginning of my trying to be what I thought people wanted to be.’

In this excerpt from her autobiography, Catch A Fire, Melanie Brown (Scary Spice from the Spice Girls) tells the world her thoughts on mixed-race. ‘I was lucky that my parents were so cool about race when I was growing up. They respected each other’s cultures and mixed them and were happy about it, which was rare. They taught me always to respect both Black and White people. I’ve since noticed that Mixed-Race kids can get really confused if there parents sway one way or the other and are prejudiced against White or Black, because they become alienated from one side or the other. It’s difficult because you’ve got your Black communities and you’ve got your White communities. There are Black churches, White churches, Jewish, Buddhist, Muslim and other places of worship, but you don’t get anything officially for Mixed-Race people. I’m not saying that being Mixed-Race is a defined culture and has a history – well, it has got a history but it’s been taboo for a long time, because society has always been so divided. For centuries, Mixed-Race children were mainly associated with being products of rape, the result of forced encounters between masters and slaves on plantations. They were ignored, their existence swept under the carpet and they were part of a forgotten history. Things have changed now. We’re starting to mix more and you get people who are quarter this, a half that and a quarter something else, which is great. The only problem is that there are a lot of kids growing up who don’t feel they belong anywhere. Their identity isn’t black or white. I had problems knowing where I fitted in sometimes. I had Black friends and I also had White friends and some of my Black friends would be completely on the Black side dissing the Whites, while some of my White friends were completely on the White side and didn’t really know anything about the history of Black culture. They had no idea about all the suffering that had gone on. I was different to the other Mixed-Race kids at school because I never chose one side over the other. I got on with everyone and as a result I was called ‘Bounty’ – Black on the outside, White on the inside. I remember thinking, Why are they calling me that? My parents had Black friends and White friends and I spent time with my mum’s family and my dad’s family, so my life was properly mixed, even down to the music I heard at home – from Aswad to the Eurythmics’

John Conteh was born in Toxteth, Liverpool, to a Sierra Leone father and an Anglo-Irish mother. Frequently in trouble as a teenager, his father steered him towards boxing. On March 13th 1973, at the age of just 21, he won the European light heavy-weight title. He went on to win a string of titles including the WBC Light heavyweight title. John said in his autobiography, ‘My first realisation that I was different from my white mates came when I was making sand castles from some builders materials in the road, that’s how young I was.A drunk loomed over me and began kicking my castles over and called me some frightening names. The one that struck the most fearful chord in my child’s brain was half caste.I remember running indoors to my mother and demanding some kind of explanation. When she told the old man about it that night, he roared like a lion, shouting: ‘My children are not half of anything. They are full human beings.’

For footballer Curtis Davies it is important that people acknolwedge all of his racial identity.’I’m as much white as I am black,’ he says. ‘People have got to acknowledge that. My mum is white and I don’t want people to discount that.’ Curtis has an older half-brother who is white. ‘Every time we went to football people couldn’t believe we were brothers,’ he says. ‘They couldn’t take that I could be related to a white person.’ For Curtis Davies having a fluid identity can also raise difficult questions. ‘If I’m walking down the street with black mates, it’s cold and we’ve got our hoodies up, we are likely to get name-checked by the police. I’ve been with my white mates, same area, same hoodies and it’s never happened. The police don’t even look or slow down. I guess that’s another aspect about the split in my race,’ he says. Curtis is aghast at the idea of having to choose. ‘Choosing which room to go into?’ he says. ‘That’s like choosing who to save from a burning building, your mum or your dad.’

Manchester United’s Welsh International winger Ryan Giggs gave a remarkably frank interview in the French weekly L’Eqipe Magazine, when he publicly acknowledged his black heritage. ‘Most people do not know that my origins are African-Welsh, in fact only the people who are close to me and who count for me know my whole story. Looking at me from the outside, it is not very obvious, I know but half my family is black and I feel close to their culture and their colour. I am proud of my black roots and of the black blood that runs in my veins. I do not wish to hide my origins, nor do I seek to make it a subject of conversation. I am what I am.’

Growing up surrounded by white faces in Welwyn Garden City in Hertfordshire, English footballer David James was the only non-white child at his junior school. ‘I was called a coon and a black bastard,’ he says. ‘I lived with my white mum so I couldn’t go back to an ethnic home and relate the experience. At school I was asked if I was adopted. I got confused and I’d go home and ask my mum if I was divorced.’ David believes that there was a direct correlation between bullying because of his mixed-race background and his low self-esteem. ‘Trying to break records in goal was all about proving that I was valuable.’ David also had a problem with the term half caste saying:’Being described in fractions is like being seen as abstract parts. It was a subtle prejudice that I felt,’ he says, ‘but people always commented on pieces of me – my hair, my colour – no one ever said anything nice about the whole of me.’

Crystal Palace winger Jobi McAnuff grew up in north London with his Jamaican father and English mother. Jobi celebrates his fluid identity, but he admits that in football there are racial cliques. ‘From my experience I get seen as one of the ‘brothers’. You walk into the canteen and there’s a table of black boys and the white boys are up the other end, but I don’t see it as a negative. I’d like to think it’s easier for me to cross between groups, but my white friends at Palace still see me as black. People only see skin deep and society says I look more black than white.’

Actress Thandie Newton tells interviewers that one of her fondest memories is watching her mother get dressed in her traditional African garb because it taught her black pride. ‘It’s funny, but yes. I was recently talking to my brother about what it means to be black, and he gave me a quizzical look, as if to say, ‘Hey, this is a bit radical,’ because I was taking a very black stance. But he reminded me of how I used to feel- as neither white nor black, but as a bridge between both. Now I see myself as black. There is a side of me that would like to go back to how I used to feel. But then I was looking at my peers. Now I’m looking at the whole world.’

Lead singer of the Pussycat Dolls Nicole Scherzinger was born in Hawaii, her father is Filipino and her mother is Hawaiian and Russian but Nicole has had many people confuse her racial identity. ‘I’m Filipino-Russian-Hawaiian,’ she says, ‘but people think I’m from Pakistan.’ She may be a household name now but Nicole remembers how difficult it was as a mixed-race girl when she was first entering the entertainment industry. ‘A lot of people didn’t understand what my nationality was or what race I was. So, they were a little confused on how to cast me or what my place was. It was really confusing at first because people wanted me to be like the Puerto Rican girl, the sidekick, the Puerto Rican best friend. I’m like, I’m not Puerto Rican.’

England women’s striker Rachel Yankey grew up in west London with an English mother; her Ghanaian father did not live with them. Sometimes it is the small things about a mixed-race background that make the most impression. ‘I’ve been in a shop with my mum and they’ve looked at both of us and gone, ‘I can see you’re related’, and I’m thinking, ‘Why say that?’ Or hairdressers, that’s the most common one. I remember going to white hairdressers with my mum and they couldn’t cut it right, or they put the wrong products in.’ Rachel says she feels uncomfortable when people assume things about her because of how she looks. She tells the story of an African mother to a child who attends her coaching sessions. ‘She brought in some traditional African food for me and asked if I knew what it was. She wasn’t quizzing me, but I felt that being half-African I should know. It bothered me that I didn’t. I felt I had to explain. I said that my dad didn’t bring me up, I didn’t grow up eating African food.’ Rachel also says her feelings differ according to the colour of the people in the room. ‘When you go in the white room you know you’re different looking, but I’ve grown up with white people so that’s probably where I’d feel most comfortable. When you go in the black room you look similar but you don’t feel as comfortable inside. I’m happiest when I’m surrounded by a mix of people.’

In a forum on what it is like being mixed race, there were many different responses:

AutoMango: No different to being any other race really. in all of primary school there was just me and a black boy who were anything. there were half german twins but they’re still white. i think at that age and a bit older people think if your not white then you’re black, which of course im not-im neither, so you get the odd childish comments. “have you been painting with black paint today?”

Kiero: Being mixed race is all about having other people arguing about your identity, and the supposed “crisis” you suffer. Along with being labelled a “coconut” if you’re well-educated and articulate.

osg_2: being mixed is a different experiencce still becos lots of ppl think ur confused or in sum way special, iv had lots of ppl sayin 2 me i wish i was mixed-race. But a bad thing is dat alot of (black) people think that mixed-race ppl thinkk there 2 nyc an r skets/slags/hoes/easy. I dnt lyk dese views

korlebu: Good points – I genuinely support France, Ghana and England in major tournaments as they have made me the individual I am

– I have the social and interpersonal skills to adapt into black or white environments (and other environments for that matter)

– My white side (mother) has done what my black side (father) was unfortunate enough not to do. Send myself and 4 other sibblings to top schools and university (cambridge etc). (Father well educated in Ghana but could only get a job as postman in UK)

– Have inherited stronger physical attributes from black side as have my 4 other sibblings (some may argue this, but science will argue my point)

– I represent how far black and white culture have come from our darkest days

– On a lighter note, sooooo many girls (especially black girls) want to have my children! Seriously, I have a queue.

Bad points

– When we lived in Ghana, we were called ‘obroni’ – white people by the black mainstream. When we came to UK, we were called black by the white mainstream.

– Black people see you as cousins or outcasts and white people see you quite simply as black or are so uneducated on the matter that they think mixed is just black but a different shade.

– Despite most mixed race (including myself) people saying to themselves that they are neither black or white but individuals, the truth is that since the caveman days we have always sought a group in society to belong to and as long as mixed race are not recognised on a more ‘official’ basis as whites and blacks are the question will always remain

Milk Maroon: Well being mixed race, it’s generally having your parents from two very different ethnical and/or cultural background. Sometimes you have to deal with the issues it can generate, sometimes you’re lucky enough to get to know both parts and cultures you’re made of.

Generally, I believe we’re more a product of our environment. That’s why you can “look black” but not relate to Blacks… There are numerous of examples, this one is one among many.

BenS: I was never told I was any race as an infant, I always knew I was mixed so in general my me being mixed isn’t an issue because I’m just me. What I dislike is the perception people have of mixed race people. Things like if a mixed race person has a white mother, then the perception is she must ugly, fat, working class etc. If a mixed race person has a white parent, he must also be ugly, but also a wimp. I also dislike the fact mixed race people are in general viewed as having identity issues, and that a well grounded mixed race person see’s themselves as black. And that mixed race people who are brought up by a single white parent, think they are white, and are somehow racist towards black people. The sad thing is these racist stereotypes are mainly things black people wish to be true. I would say these are the general stereotypes of what it’s supposed to be like to be mixed race. They only stereotype I fit is that from the age of 4yrs old I didn’t grow up with my black father, so the stereotype of growing up with a single white mother (though a very beautiful and middle class one) is true for me. But from my own experience, I me being mixed race isn’t an issue unless I’m around black people who have these “what are you” attitude which which I find very offensive. Though it’s wrong to presume every black person has that attitude. The black and white view of mixed race people as a whole I guess is from what I read online and tv documentaries etc is, that white people don’t wish to admit we are part of their “pure” culture. And that black people want to control use and have use deny our European side.

Born to a Nigerian father and White mother, Sir Keith Ajegbo is a key figure in education in Britain, as a former headmaster and author of the report to the Secretary of State for Education and Science on diversity and citizenship within the school curriculum. In a post for the Mixedness & Mixing website which gives new perspectives on mixed-race Britons, he said “The spectrum of being mixed race is extremely wide. It is dependent on the particular racial mix, on location and a range of other factors. However a very crucial component to mixed race children belonging and feeling whole has to be the attitude of their parents. My unresearched observation is that if parents are sensitive to their child being mixed race and are prepared to work together on the issues that might arise in terms of identity and belonging then this makes a considerable difference. I expect it also makes a difference if the family is together and both races are part of that family experience. The biggest psychological issue for me was being part of a white family with very little contact with the black side of my family. While my white family were very good to me they treated me as if I was white but had, rather accidentally, black skin. My grandmother would never allow black people into her house because of the trouble caused by my mother’s marriage. I remember my mother telling me to pull my cap on so people couldn’t see my hair and crying when my aunt referred to my curly hair. As a result I have always felt an element of being outside both races and of being inauthentic. There are geographical contexts. It is probably easier to be mixed race in London, which is increasingly multi cultural, than Bradford and other cities where Trevor Phillips has talked of the country ‘sleepwalking to segregation.’ Nor is it easy to be ‘the only black in the village’. One way in which being mixed race has determined my life is that I couldn’t move out of London because I imagine I would not feel comfortable. It is also true that the nature of a person’s mixedness make a difference. There are different issues for children of mixed African Caribbean or African and white heritage which is quite common in some urban areas to children of Asian/white heritage. Class makes a difference. A purely personal observation is seeing working class mixed race pupils moving towards black youth cultures and middle class mixed race pupils moving towards white. In terms of schooling and neighbourhoods working class pupils often come into far greater contact with pupils from other cultures. This is exacerbated by white middle class flight. I have often felt disturbed by TV satires around working class culture that imply a mongrel society. While some aspects of being mixed race are easier as the society becomes more at ease with race and difference, mixed race children are still likely to be at the sharp end of tensions and prejudice. An issue for me, which I expect is still there, is for mixed race children to have to listen to prejudices voiced by one or other of their races against the other one. This can create a real sense of dislocation and being an outsider. One of my great fears as a child, which has recurred through my life, was of a great war between white and black in which I could find no haven on either side.”

The media are also paying a lot more attention to the mixed race ethnicity. In a 2006 article for The Guardian newspaper, Laura Smith talked being mixed race: “Aged seven, I had the dubious distinction of being the only girl with one pink and one brown parent at my north London primary school. Although rarely intentionally unkind – apart from the little boy who called me poo in the school playground when the mood took him – my all-white classmates never let me forget that I was not like them. They asked me what it felt like to be black and touched my hair uninvited. In turn, I cut off my curls as gifts to satisfy their curiosity and told them that where my mum came from they cleaned their teeth by chewing on sticks. Nearly 25 years on, much has changed. The last national census counted 680,000 mixed race people, accounting for 1.2% of the overall population and nearly 15% of the ethnic minority population – and that is widely believed to be an underestimate. Suddenly, our image is everywhere, projected on posters selling Marks & Spencer’s bikinis or sofas for DFS. Mixed-race people have become the acceptable face of ethnic minorities for advertisers and programme makers. We are sufficiently exotic for viewers and consumers to recognise as “other”, and therefore a handy shorthand for diversity without the potential alienation associated with using somebody too black, too different, too dangerous. And yet there is an inconsistency. Despite our growth in numbers and our incredible visibility, we are utterly absent from any public debate on race. We appear to be the elephant in the room: obvious to anybody living in a large British city yet invisible at a government level. Take the current discussion surrounding multiculturalism. The fact that people are increasingly falling in love, or simply in lust, and having children across a so-called racial divide is an inconvenient truth that challenges the government’s notion of neat “communities” of black, white or Asian people.” [to read the full article, see the links at the bottom of this post]

Being mixed race is very different from other any other race and has both its advantages and disadvantages. I believe however that as this ethnicity grows and becomes more common, eventually being mixed race will become as normal as being Black or Asian or White and perhaps my future mixed race grandchildren will have completely different experiences to myself, just as I have had different experiences to people like Sir Keith Ajegbo who grew up in the 1950s and 60s.

Information from:

Melanie Brown’s autobiography Catch A Fire

In today’s world, our race or ethnicity has an enormous effect on our personal identity. Races have histories, celebrations, countries of origin, cuisines, music styles and more. Mixed race, or biracial people have ancestries which come from different races. Technically, we are all multiracial as people boast of being “1/3 Italian, 1/5 French with a Grandma from Scotland” but the term mixed race/biracial refers to those with parents from two different races.

In today’s world, our race or ethnicity has an enormous effect on our personal identity. Races have histories, celebrations, countries of origin, cuisines, music styles and more. Mixed race, or biracial people have ancestries which come from different races. Technically, we are all multiracial as people boast of being “1/3 Italian, 1/5 French with a Grandma from Scotland” but the term mixed race/biracial refers to those with parents from two different races.